Global View Investment Blog

How We Select, Categorize and Fire Managers (updated November 2018)

“Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.”

- Warren Buffett

In Short

Because I know investors (and often advisors) do this wrong, I wrote this blog to explain how we pick Investment Managers.

Because it is what they are trained to do, we know that Pension Consultants use “investment fiduciary” principles to fire managers. And we know this results in poor performance. The problem is that retail investors and advisors unknowingly follow these same, flawed principles, which leads to substantially poorer relative performance.

Global View has a stringent set of quantitative and qualitative criteria for selecting, categorizing and firing any of our managers. Instead of being based on a single variable, performance, our process is based on a number of factors. And we know that this leads to higher odds of having a good outcome. Which means this process can lead to a more secure retirement.

How We Do NOT Select Managers

Unlike insurance companies and brokerage firms, we will never hire a manager because the manager pays us. How terrible that, for example, insurance firms can select investment managers in life insurance and annuity accounts based on how much of their revenue they will share!

We are fee-only advisors paid only by our clients. This means we will never be influenced by this.

Moreover, we will not pick funds based on how they performed recently. I completed the Accredited Investment Fiduciary program in October of 2008 because I wanted to know how so-called “investment fiduciaries” pick funds. I did not renew my designation as an Accredited Investment Fiduciary, because I do not believe their practices add value. In fact, I believe they destroy value.

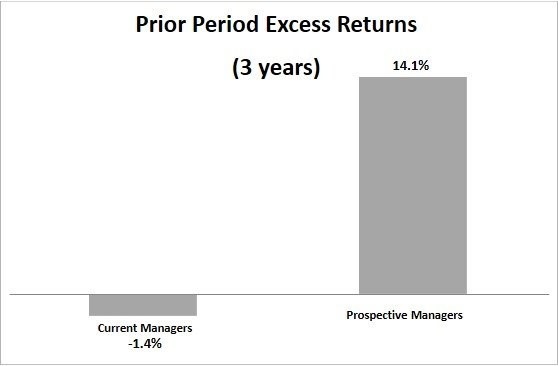

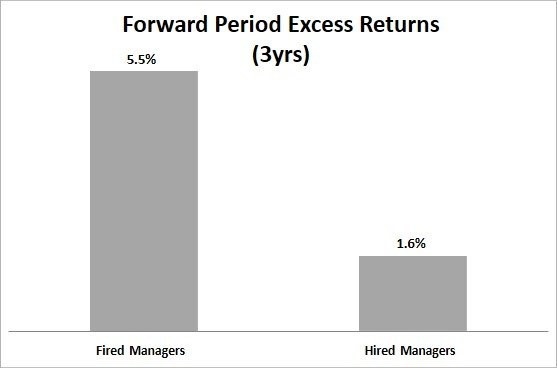

A paper written by Wahal and Goyal at Emory University called “The Selection and Termination of Investment Management Firms by Plan Sponsors” reviewed the practices of 3,500 plan sponsors during a 10-year period. The study concludes (on page 39) “plan sponsors terminate investment managers after poor performance but the performance of these (fired) investment managers appears to rebound after firing.” The principles leading to this trend of poorly timed terminations is taught in the Accredited Fiduciary program.

This is a cautionary tale to be very slow to fire a manager if you believe in the manager’s investment process. Sometimes managers are just lucky, and sometimes they are unlucky.

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, below are two charts showing the prior excess returns of the managers (before they were fired) and the subsequent excess returns. We know retail investors do this as well (see our paper on investORs vs. investMENTs), so clearly it is an area an advisor can add value IF THE ADVISOR DOESN’T DO THIS TOO!

Firing Based on Recent Performance Usually Backfires

Contact us for more information.

How We Select Managers

For equity managers, we strive to find strategies that will deliver a high absolute return over an expected investment horizon of three to five years and beat 10 percent p.a. over the long-term. For the lower risk bond managers seek investments we believe will do better than the bond market indexes with similar (or maybe a bit more) risk. We want these managers to be positive most of the time.

To accomplish these two objectives, we screen the universe to find managers whose primary motive is always to avoid losing money that cannot be made back.

The easiest way to know this is to hear the manager say it and include it in their marketing message.

We believe, that if you can look anywhere around the world, and in the case of bond managers, you can look at private and public debt, that you have a much greater pool to fish from. This means there is always something to do, to quote Peter Lynch. Sometimes, some markets get ahead of themselves leaving little to do. When this happens, it inevitably leaves others behind, creating opportunity.

A happy byproduct of this is often lower downside risk versus indices and higher long-term returns. We noticed this happened during the 2000-2002 bear market (not over shorter periods but from top to bottom) and during the 2008-2009 bear market.

We look at the following criteria to select the relative attractiveness of our managers:

- Demonstrated adherence to Margin of Safety investment objective (avoid losing money you can’t make back)

- Shareholder first attitude (willing to close to new investments, more interested in client wealth than own)

- Asset size (smaller is generally better)

- Flexibility (ideally can invest anywhere in any market capitalization)

- Own cooking eaten (managers have substantial stake of their own net worth in their fund)

- Manager’s long-term track record: The manager (as opposed to the fund) has an excellent track record managing investments

- Stated return objective: We read and listen to almost everything our managers say. They try to hedge, but often let their return objective slip. We believe you need to have a goal to achieve it.

- Downside Reduction Goal: Some managers are less concerned about volatility than others. Only those managers most concerned about managing downside risk will be included in our lower-risk bond stable

We add managers when new opportunities arise. We know the track record of the manager and his analyst team is the driver of investment performance more so than the firm where he may have worked. For this reason, when we see a manager start a new company or fund, we are quick to perform due diligence and add this to our mix. Two examples of this are the IVA Worldwide (IVWIX) fund and Grandeur Peaks Global Opportunities (GPGIX). We chose these funds based on the incredible risk adjusted track record of Charles deVaulx and Chuck deLardemelle at IVA and of Robert Gardiner at Grandeur Peaks and because we believed in their process. “Pension Consultants” and retail investors looking for a three-year track record would have been out of luck because both funds closed to new investors before the funds had a three-year track record.

More recently, we added Centerstone, managed by former First Eagle Global Portfolio Manager Abhay Deshpande, and others.

How We Categorize Managers

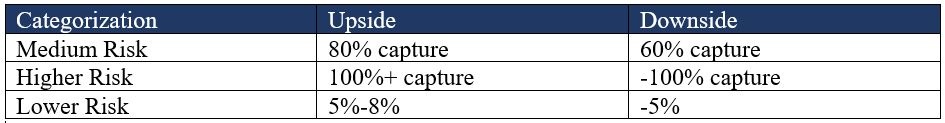

We put managers into three categories: Lower Risk, Medium Risk and Higher Risk.

Lower-Risk managers are primary bond funds who seek to make positive returns most calendar years and to be up or down less than equities during bear markets. Medium-Risk managers will have lower downside risk than equities but similar return characteristics over full market cycles. Higher-Risk Managers may have the same downside risk as equity indexes but should produce higher returns over full market cycles.

We categorize our managers into three buckets.

How We Fire Managers

There are really three reasons we will fire a manager. The first, and main reason, is that we believe the manager is not concerned about losing money that cannot be made back (is not seeking a “margin of safety”). The second reason we fire a manager is when we recognize the manager is not fulfilling our stated objective (the main reason for this is that the manager has become more concerned about being “right” than reacting to a changing environment). The final reason for firing a manager is to replace the manager with a better manager. This can happen for many reasons, only one of which is performance.

A great example of firing a manager for losing sight of his primary focus to avoid losing money that cannot be made back is the Oakmark fund. We fired this Bill Nygren in September 2007 after we discovered he was wrong in his investment thesis, probably due to hubris. He continued to talk about Washington Mutual as a good investment, avoiding subprime. But our own research (from the Q3 2007 10Q) revealed the company had gotten more heavily into subprime. Washington Mutual subsequently went out of business and Oakmark fund investors suffered.

Another great example of firing a manager for losing sight of his primary focus to avoid losing money that cannot be made back is the Hussman fund. John Hussman used excellent logic to support his thesis, but unfortunately, this resulted not just in underperformance but negative performance.

A great example of replacing a manager is Rondure Global. Before Laura Geritz teamed with Grandeur Peak, we didn’t have access to a focus primarily on emerging markets. We used a fundamental index fund until she opened Rondure Global.

Conclusion

We know we won’t always get this right, particularly in shorter time intervals. We also know what drives returns. And if we can avoid negative biases distracting us from our targets, we only need to remain vigilant. Our vigilance must be focused on our fiduciary duty to our clients. If we spot that we are wrong about a manager, we will admit this and make a change. But this analysis will always be based on multiple criteria, as outlined. It will never be based on short-term performance alone.

Written by Ken Moore

Ken’s focus is on investment strategy, research and analysis as well as financial planning strategy. Ken plays the lead role of our team identifying investments that fit the philosophy of the Global View approach. He is a strict adherent to Margin of Safety investment principles and has a strong belief in the power of business cycles. On a personal note, Ken was born in 1964 in Lexington Virginia, has been married since 1991. Immediately before locating to Greenville in 1997, Ken lived in New York City.

Are you on track for the future you want?

Schedule a free, no-strings-attached portfolio review today.

Talk With UsPopular posts

-

-

-

-

.jpg) Roth Conversions: When They Make Sense and What You Should Consider by Matthew Crider January 07, 2026

Roth Conversions: When They Make Sense and What You Should Consider by Matthew Crider January 07, 2026